Cardi B Wins Jury Verdict against Tattooed Plaintiff

By Jennifer E. RothmanNovember 1, 2022

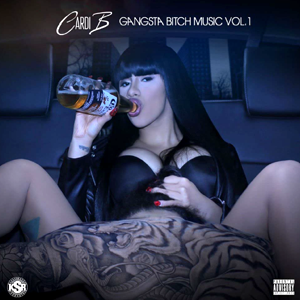

On October 21st, in Brophy v. Almanzar, a jury sided with recording artist Cardi B (aka Belcalis Alamanzar) and rejected a lawsuit brought against her by Kevin Michael Brophy. The dispute arose out of the use of Brophy’s tattoo as a starting point for the cover art of Cardi B’s “career launching” 2016 mixtape Gangsta Bitch Music Vol. 1.

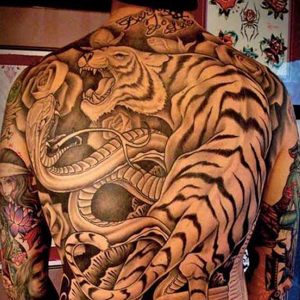

Brophy’s tattoo was photoshopped onto the back of another man, who appeared to be performing oral sex. Brophy contended that because of the uniqueness of the “tattoo across his entire back depicting a tiger battling a snake,” he was readily identifiable from the use even though he was not the person who appeared on the cover. Brophy alleged that not only was his likeness commercially exploited without his permission, but he was also subject to “ridicule,” “humiliation,” and shame because of the salacious context in which he seemingly appeared. Brophy filed suit, bringing claims for the violation of both his statutory and common law right of publicity under California law, as well as a false light claim against Cardi B and the other defendants (Washpoppin, Inc., KSR Group, and Does 1-20). (Brophy and his tattoo are below, as well as the cover at issue.)

In earlier decisions, the district court rejected defendants’ arguments that the complaint failed to state a claim, that the use was protected by the First Amendment, and that the claims were preempted by copyright law. The court sent to the jury both the prima facie case and the First Amendment defense. In both motion to dismiss and summary judgment opinions, the court concluded that the use was not transformative as a matter of law. Instead, the judge sent the determination of transformativeness to the jury. Brophy v. Almanzar, 2020 WL 8175605 (C.D. Cal. 2020); Brophy v. Almanzar, 2019 WL 10837404 (C.D. Cal. 2019).

The jury, however, did not reach the First Amendment defense. (Jury Verdict.) Instead, the jury rejected the claims outright. The jury verdict form was quite broad but indicates that the jury thought that there was no misappropriation of Brophy’s likeness, nor violation of Cal. Civ. Code § 3344, nor a portrayal in a false light.

Because of the general nature of the jury verdict form questions, one needs to do a bit of tea-leaf reading, cross-referencing the jury instructions, and reading some reporting on the trial to garner the likely basis for this outcome. The most likely explanation stems from some reports that Brophy did not bring anyone into court who had recognized him from the cover art. One can surmise that his complaint might have referred to reactions of people to whom he pointed out that his tattoo was used on the cover, but by doing so these people would simultaneously learn that Brophy was not in the photograph.

The jury instructions themselves also created a likely insurmountable hurdle for Brophy, and perhaps unfairly so. For the common law misappropriation claim, the jury instruction required the jury to find that Brophy’s “likeness or identity” was used on the cover art but did not provide further guidance as to what this analysis requires. Notably, the instructions do not suggest that the tattoo itself could meet this requirement if it evoked his identity or confused viewers into thinking that he appeared in the picture even if another man was the one in the photograph. (Instruction 17.) If a robot in a blonde wig qualifies as evoking a person’s identity, certainly using a tattoo that points uniquely to a particular person would count too. If people had recognized Brophy from the tattoo, and thought that was him on the cover, the claim should have succeeded. Brophy should not have to be famous to win such a case. Instead, as other California courts have suggested a person need only be readily identifiable by people familiar with the person.

The jury instructions were also likely hard to follow as to the requirement that the defendants must have gained some “commercial benefit or some other advantage by using Mr. Brophy’s likeness or identity.” (Instruction 17.) This language suggests that the jury may have thought Brophy’s identity needed to have value in particular—which seems somewhat absurd in the face of a mega popstar’s own value. But the value of using his tattoo and not needing to create their own or hire a model has long been sufficient to make out a common law claim.

The Section 3344 claim was a higher hurdle for Brophy because it does require the use of a person’s actual likeness, rather than the broader persona claims allowable under the common law. However, if the use of the tattoo made it seem as if his likeness was used, this would have been sufficient under the statute if he had evidence that people (mis)identified him as the person on the cover.

Another challenge for the 3344 analysis was that the jury instructions suggested that the use of his likeness needed to be to “advertise or sell” the mixtape and that the use had to be “directly connected to Cardi B’s…commercial purpose.” (Instruction 18.) This could make it seem as if the use of his identity had to be because of Brophy’s extrinsic marketplace value to Cardi B—again, something that would strike the jury as unbelievable—rather than that the use simply needed to use his likeness “on or in products, merchandise, or goods” which she unquestionably did. See Cal. Civ. Code § 3344. In addition, cover art has been considered in other cases as a form of advertising and promotion.

I am not sure that better instructions would have changed the outcome here, but it is a good reminder that members of juries are not experts on right of publicity law and there are lots of pitfalls in jury instructions like these that don’t clarify the likely wrong turns jurors can take evaluating such claims.

Even so, I am doubtful there will be an appeal in this case given news coverage that Brophy went up to Cardi B at the end of the trial shook hands and said he "respect[ed her] as an artist." Perhaps he is simply hoping to avoid paying her attorney’s fees.

Although the jury didn’t reach the question, the jury instructions on the First Amendment defense asked the jury to consider if the mixtape cover added “something new to Brophy’s likeness, giving the likeness a new expression, meaning, or message,” if so, the use was transformative. This is a broad take on transformativeness, and it seems likely that the jury with that framing would have decided the cover art was transformative.

It will be interesting to see how the analysis of transformativeness in right of publicity cases may shift depending on the outcome and analysis of the Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith, in which the Court is likely to revisit the role of transformativeness in copyright’s fair use analysis.

Speaking of copyright, a copyright claim arising out of the use of the tattoo in the cover art might have been more successful, though no such claim was brought by Brophy (who likely doesn’t hold that copyright) and I have not seen such a claim by the tattoo artist. I note that many media outlets reported Brophy’s claim as including a copyright claim, but it did not.