First Amendment Protects Use of Videogamer’s Likeness in Cartoon Network Animated Series

By Jennifer E. RothmanNovember 24, 2015

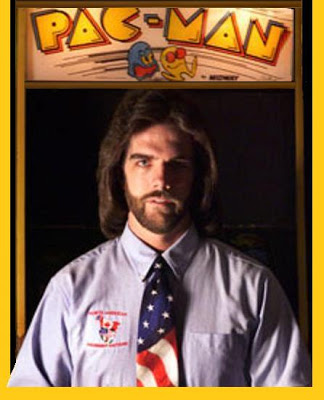

Billy Mitchell, a well-known videogame player with world records for classic arcade games like Donkey Kong and Pac-Man, sued Cartoon Network for allegedly using his likeness for a character in The Regular Show. The animated comedy series follows two animals, a blue jay and a raccoon. In one episode, titled High Score, a character named Garrett Bobby Ferguson (“GBF”) appears as a “giant floating head from outer space” with similar hair and beard to the plaintiff, who also shares his status as a record-holding videogame player. GBF appears in several other episodes as well. Not pleased with the portrayal, Mitchell sued for misappropriation of his identity under New Jersey law. Cartoon Network conceded that the show was referring to Mitchell, but contended that it was parodying him and that the use was protected by the First Amendment. On Friday, a federal district court in New Jersey agreed and dismissed the claim. The court applied the “Transformative Use Test” which it described as a balancing test. Here the court held that the defendants had added “something new” and the use was not “merely a copy or imitation.” The court therefore concluded that the use was protected by the First Amendment. The court analogized to the California Supreme Court's decision in Winter v. D.C. Comics that held the use of the plaintiffs' identities in a comic book protected by the First Amendment. In Winter, the identities of musician brothers, Johnny and Edgar Winter, were transformed into worm-like creatures, and their name to Autumn, leading the California court to conclude that the work was transformative. The court also distinguished Mitchell's case from the Third Circuit’s recent decision in Hart v. Electronic Arts that the use of athletes’ identities in a videogame was not protected when those players were accurately depicted. Although the court properly dismissed Mitchell's claim, its analysis accepts the problematic disfavoring of realistic depictions of individuals in expressive works. The court suggested that if Mitchell had not been transformed into a floating giant head, then the use might have lost its First Amendment protection. Again, the Supreme Court needs to step in to the fray here and grant certorari in Davis v. Electronic Arts to provide sufficient First Amendment protection for realistic portrayals in expressive works. Otherwise, this case demonstrates that realistic depictions in television series may be in jeopardy.

Mitchell v. The Cartoon Network, Inc. (D.N.J. Nov. 20, 2015)