Olivia de Havilland Back in the Spotlight

By Jennifer E. RothmanJuly 5, 2017

One of Hollywood’s most successful plaintiffs and actresses is at it again. Olivia de Havilland, the two-time Oscar winner, who appeared in such Hollywood classics as Gone with the Wind and The Heiress, has sued FX Networks and Ryan Murphy in California Superior Court over her portrayal in its miniseries Feud. She claims that the series violates her rights of publicity and of privacy, and that the producers were unjustly enriched by the use of her name and personality.

De Havilland, now 101 years-old, hasn’t lost her penchant to seek justice in the courts. She fought with Jack Warner in the 1930s and 1940s to get out of her oppressive contract with Warner Brothers. Eventually, she won her court battle and forever broke Hollywood’s star system by invalidating the contracts that actors signed tying them to particular studios.

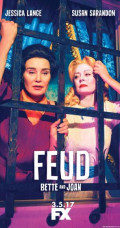

Feud is sure to win awards this coming Emmy season for its gripping tale of the ongoing conflicts between Hollywood heavy-hitters Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Susan Sarandon and Jessica Lange will likely be nominated for their performances in those roles. But de Havilland was not pleased with her portrayal in the series.

Catherine Zeta-Jones played de Havilland. The de Havilland character was not a major part of the series, but instead primarily appeared in short interviews in a mock documentary used as a framing device. De Havilland objects to being included in this faux documentary which she says did not take place and which she thinks tars her as a gossip. She also objects to several other scenes in which she is portrayed as insulting her sister, Joan Fontaine, with whom she is alleged to have had a strained relationship. De Havilland appears particularly incensed by the fictional de Havilland’s use of the word “bitch” to describe Fontaine.

For what it is worth, this viewer of the series thought de Havilland was depicted exactly as she describes herself in her complaint. She was portrayed as a person with class who did not want to participate in idle gossip, even when goaded into doing so by others. The suggestion in the series that in private moments and in conversations with a close friend, she might have been less varnished in her assessments of her sibling, who had said unkind things about her to the press, does not in any way diminish her reputation.

Surprisingly, despite the main gravamen of the complaint being a false light or defamation claim, neither claim appears in the complaint. Perhaps, given the Supreme Court’s longstanding speech protections for fictionalized plays and movies in the context of such claims, her lawyers saw this as an uphill battle. (see Time v. Hill).

But those causes of action likely would have more traction, than the ones she does bring. The statutory right of publicity claim will not apply to Feud since the miniseries will not be understood as a product, merchandise, goods or as an advertisement.

The common law publicity and privacy claims also are likely to fail on free speech grounds. The use of her identity was newsworthy and in the public interest, and should either fall outside of such state laws or be allowed by the First Amendment, whether under California’s transformativeness test or strict scrutiny review. The use may also be deemed an incidental use, rather than one for the defendant’s advantage given the lack of focus in the series on de Havilland's identity.

One can’t help but worry though that what should be a slam dunk First Amendment defense, has been made less so by the 9th Circuit’s recent decision in Sarver v. Chartier. The court in Sarver suggested that portrayals of those with commercially valuable identities in films might be treated differently than portrayals of private figures. The Ninth Circuit probably did not mean what it said in that regard, but was stuck trying to navigate around the Davis v. Electronic Arts and Keller v. Electronic Arts decisions that held that a videogame could not include realistic depictions of student-athletes.

The California state courts, however, in which this lawsuit was filed, have been very protective of movies and the use of real-life public figures in them. I suspect the same will be true here.

When push comes to shove though, one should never count de Havilland out.